Previous Chapter: Flying In

Contents

Chapter 2. El Zocalo

Mexico City has some extremely wide roads, cars drive

maniacally down eight lanes in one direction, jumping lights with

impunity. The streets have the India look - plenty of small

establishments, unlike the mall-obsessed US. For those who knew my

M-80 scooter-moped: I even spotted clones of that in DF. Honda and

Suzuki motorbikes were gleefully polluting the air just like in India.

In the third world, two-wheelers are the middle-class's liberation from the

vagaries of public transport; in the west, it's cult-symbol.

The Zocalo, a big square with the Mexican flag flying in the middle, is the heart of

the city, and from the tourist's point of view,

presents a good preview of its most interesting aspects. The roads along its perimeters

are dominated by Volkswagen Beetles - the original rear-engined one, still manufactured

in the Mexican VW plant, not the Golf in slick retro garb advertising its owner's

"funky" taste in color canary. The green beetle taxi, scurrying about, robbing passengers,

running down pedestrians, unhesitatingly doing half a kilometer on reverse gear along

one-way streets, imparts Mexico City its image.

The Zocalo, a big square with the Mexican flag flying in the middle, is the heart of

the city, and from the tourist's point of view,

presents a good preview of its most interesting aspects. The roads along its perimeters

are dominated by Volkswagen Beetles - the original rear-engined one, still manufactured

in the Mexican VW plant, not the Golf in slick retro garb advertising its owner's

"funky" taste in color canary. The green beetle taxi, scurrying about, robbing passengers,

running down pedestrians, unhesitatingly doing half a kilometer on reverse gear along

one-way streets, imparts Mexico City its image.

On the south of the square was a big, official-looking building, extending a

colonaded arcade over the sidewalk.

It was about noon, and people we presumed to be government employees hung about in

groups, picking their post-lunch teeth and discussing the situation. We were wondering if

this colonial building would be the Palacio Nacional with its famous Diego Rivera

murals, and if so, would they have restrooms within? Poking our noses into a wrought

iron gate, we could spot neither murals nor facilities, and gathering the

impression that our identities might be peremptorily challenged by a nasty, helmetted guard,

quickly withrew our necks. Here and there in the city, trucks of helmetted soldiers,

sometimes in riot gear, evoked the chilling archetype of a Latin American country

where people were picked up and never came back. ( "If somebody from your family

disappeared, you hate Pinochet" - yeah, right.)

We figured that the best strategy would be to make a circle

of the square - the Palacio ought to be somewhere along the way.

With buildings on all four sides of it, the only roads leading into and out of the square

are at the corners. At noon, traffic was both heavy and chaotic. We wended our way along

narrow chinks between vehicle bumpers, a technique the suburban American would find

most hazardous. A number of rickshaws, of the usual bicycle-converted-to-tricycle design

seen in India, were parked at the north-eastern corner - few were plying the roads, and

fewer still were actually carrying passengers. We didnt spot rickshaws anywhere else

in the city; so I wonder if these are a poor man's horse-carriages at

Central Park. This corner of the Zocalo appeared closed to traffic, and a fairground

atmosphere had taken over. Vendors ranged from sellers of charms to snacks. Beaded men

circled smoking braziers around their clients' heads in occult ceremonies. One of them

took off his sombrero and shielded

himself with it when I attempted to photograph him performing a proprietary

ritual. The snack-sellers sold an extra-large version of the Indian papad (a paste of

lentil grain, rolled out thin, dried in the sun and deep fried in whatever medium).

With buildings on all four sides of it, the only roads leading into and out of the square

are at the corners. At noon, traffic was both heavy and chaotic. We wended our way along

narrow chinks between vehicle bumpers, a technique the suburban American would find

most hazardous. A number of rickshaws, of the usual bicycle-converted-to-tricycle design

seen in India, were parked at the north-eastern corner - few were plying the roads, and

fewer still were actually carrying passengers. We didnt spot rickshaws anywhere else

in the city; so I wonder if these are a poor man's horse-carriages at

Central Park. This corner of the Zocalo appeared closed to traffic, and a fairground

atmosphere had taken over. Vendors ranged from sellers of charms to snacks. Beaded men

circled smoking braziers around their clients' heads in occult ceremonies. One of them

took off his sombrero and shielded

himself with it when I attempted to photograph him performing a proprietary

ritual. The snack-sellers sold an extra-large version of the Indian papad (a paste of

lentil grain, rolled out thin, dried in the sun and deep fried in whatever medium).

In India, shoeshiners squat on the road, while clients put up their feet

(one at a time) on a box for the shoes to be polished. Not so in Mexico: the customer

gets to sit on a proper chair on a raised platform, shielded from the rigors of the

elements by a shade, free to gainfully employ his time reading the newspaper. The

umbrella-like shade carries commercials on its valance. The shoeshine does his job

from a seat at the client's feet.

In India, shoeshiners squat on the road, while clients put up their feet

(one at a time) on a box for the shoes to be polished. Not so in Mexico: the customer

gets to sit on a proper chair on a raised platform, shielded from the rigors of the

elements by a shade, free to gainfully employ his time reading the newspaper. The

umbrella-like shade carries commercials on its valance. The shoeshine does his job

from a seat at the client's feet.

Leaving this hubbub behind, we entered the gate of the Palacio Nacional, which occupies

the eastern side of the Zocalo. The area open to tourists is a large courtyard with

two floors of offices all around. Quiet and peaceful in contrast to the outside,

only a few tourists around, it houses the Presidencial offices (in a different wing)

and, of more interest to us, murals by Diego Rivera. But first -

"Donde estan los banos?" - where are the loos?

Leaving this hubbub behind, we entered the gate of the Palacio Nacional, which occupies

the eastern side of the Zocalo. The area open to tourists is a large courtyard with

two floors of offices all around. Quiet and peaceful in contrast to the outside,

only a few tourists around, it houses the Presidencial offices (in a different wing)

and, of more interest to us, murals by Diego Rivera. But first -

"Donde estan los banos?" - where are the loos?

Relieved, we were able to concentrate on the murals. The most important thing about

this medium is that it's public art: Diego Rivera painted these on the walls of public

buildings in order to directly communicate with his countrymen: tell them about the

turbulent history of their land - the pre-Columbian civilizations; the invasion of

Cortez; the birth of the Mestizo people from the union of the conquerors and the

conquered in a colonization that changed the anthropology, the lingua franca of

region; the American invasion; the Mexican revolution. Such a large and complex

subject requires a suitably large canvas, and a sufficiently diverse audience: Diego

Rivera found both on three sides of the grand staircase at the Palacio Nacional.

Other murals show day to day lives of people: weavers, dyers, farmers, Wall Street

stockbrokers; despite the fact that the figures and faces make no pretense to

photographic reality, one feels very much in touch with the subjects.

The series of murals comes to an abrupt end halfway along the eastern wall; Rivera

was unable to complete the work. The largest body of his work is to be seen at

the Secretariat of Public Education, a couple of blocks away: two patios, three

floors of government offices, bureaucrats and murals. Most of it is Rivera's work,

some executed by assistants, some by other painters. A restorer seated on a scaffolding

was painstakingly cleaning a mural, square-millimeter by square-milimeter; he asked me

if I was a reporter when I took a picture of him at work.

On the northern side of the Zocalo

is the crumbling, sinking Metropolitan Cathedral, exterior of bombed out appearance,

interior a maze of steel trying to shore up the structure, holding up its

journey towards the centre of an earth hollowed out by removal of water.

Next to the charm-doctors, a group of costumed Indians danced to the beat of a drum.

Trying to photograph members of this fast-moving group with a long lens made me painfully

aware of the limitations of a manual focus camera. Behind the dancers, further into the

north-eastern corner of the Zocalo, was the Templo Mayor site. Excavation is going on

at this place, and while you dont get to see an actual temple, there is a wonderful

museum at the site. The prize exhibit was an 8-ton stone disk, undamaged except for a clean

diametric crack, discovered during repairs on electric lines under a nearby bookshop,

prompting a fullscale excavation. It is a huge bas-relief work, representing

the dismembered body of an Aztec goddess vanquished in celestial power struggle. The disk

is placed on the floor, and I was cribbing how could they possibly expect anyone to

get a good view of the whole thing, why not place it vertically? That was before I looked

up and saw a neat circular window in the ceiling, and people peering down from the floor

above. This exhibit was difficult to tear oneself away from; I came back to it for a

final look after going through the rest of the museum. The artist's achievement was to

be able to simultaneously present, both a vision of the whole, the dismemberment, and the

dynamic of a battling figure. Where should you kick yourself hardest for not carrying a

tripod? In a Mexican museum.

Ancient Mexican art is so good that it makes you realize that, unlike in science, there can

be no notion of improvement over time in art. Quantities of artifacts that I saw in Mexico

are in the same level of incomparability as the best of, say, Rodin, van Gogh, Picasso.

Each age constructs its own conventions,

of style and medium, and working within them, while breaking its predecessors' with great

fanfare, makes art. And the best of it goes beyond its boundaries of time and

convention to appeal to all sensitivities.

Who, then, was the sculptor of the disk of Coyolxauhqui? Was he

feted as the Picasso of his age? Did he make speeches on his vision of art, have his word

taken down as artistic gospel, was sought after by rival nobles to decorate their homes?

Did his society treat artists better than Mozart's treated musicians - a mere servant,

employed to perform? What were his other works? I find it a great pity that such great

art is labeled merely - n AD, x period. Emerging from the admiring reverie, I realize

how sparse archaeological evidence usually is, and that we should be glad that the artifact

should have survived and been discovered. We grant the artist the anonymity of the inventor

of the Zero.

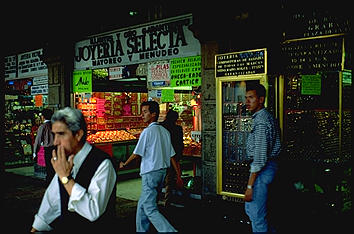

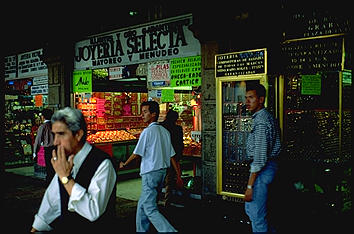

Shops, mostly jewelers, occupy the western side of the Zocalo. These establishments

double as pawnshops, in competition with the National Pawnshop in the same block.

I went in with the hope of picking up a bargain Spotmatic, only to get accosted by

freelance moneylenders hoping to cash in on the out-of-luck tourist for my pains.

The National Pawnshop deals only in traditional stuff - jewelry, watches, crockery.

An ATM was located within the establishment presumably for the service of those

come to redeem the family gold; it had a long queue - evidence of the turnaround

of the Mexican economy?

Shops, mostly jewelers, occupy the western side of the Zocalo. These establishments

double as pawnshops, in competition with the National Pawnshop in the same block.

I went in with the hope of picking up a bargain Spotmatic, only to get accosted by

freelance moneylenders hoping to cash in on the out-of-luck tourist for my pains.

The National Pawnshop deals only in traditional stuff - jewelry, watches, crockery.

An ATM was located within the establishment presumably for the service of those

come to redeem the family gold; it had a long queue - evidence of the turnaround

of the Mexican economy?

Before collapsing to our hotel rooms that night, we had one more thing to do:

the tickets for the bullfight on Sunday go on sale on Thursday, and we didnt want

to take any chances; took a taxi, landed up at the stadium, and found that this was

one of the few instances where the Lonely Planet missed an essential detail - tickets

for the best seats dont go on sale till Saturday. Dinner that night was taken at

the small San Diego restauant itself - the waiter was a nice guy who doubled as bartender,

and from his long disappearances into the kichen, we wondered if he was the cook

too. Revathi went through the menu phrase-book in hand and decided that

her fallback strategy was the best: "Quiero frijole (a bean paste), guacamole

(avocado paste), tacos". Chef was taken aback for a moment, took in a gulp, and

announced - "Preparamos!" - we'll make it for you.

View/Add Comments

Next Chapter: Teotihuacan

shayok@hotmail.com

![[Aaddzz Tracker]](http://tracker.aaddzz.com/tracker.cgi?id=11279)

The Zocalo, a big square with the Mexican flag flying in the middle, is the heart of

the city, and from the tourist's point of view,

presents a good preview of its most interesting aspects. The roads along its perimeters

are dominated by Volkswagen Beetles - the original rear-engined one, still manufactured

in the Mexican VW plant, not the Golf in slick retro garb advertising its owner's

"funky" taste in color canary. The green beetle taxi, scurrying about, robbing passengers,

running down pedestrians, unhesitatingly doing half a kilometer on reverse gear along

one-way streets, imparts Mexico City its image.

The Zocalo, a big square with the Mexican flag flying in the middle, is the heart of

the city, and from the tourist's point of view,

presents a good preview of its most interesting aspects. The roads along its perimeters

are dominated by Volkswagen Beetles - the original rear-engined one, still manufactured

in the Mexican VW plant, not the Golf in slick retro garb advertising its owner's

"funky" taste in color canary. The green beetle taxi, scurrying about, robbing passengers,

running down pedestrians, unhesitatingly doing half a kilometer on reverse gear along

one-way streets, imparts Mexico City its image.